Archetypes, part 2

The Why of an Archetype is its most interesting aspect

Colleen Barry has a story today on Instagram in which she’s talking about archetypes. Colleen’s always interesting, particularly because she really knows what she’s talking about, but we’re not always on the same page.

She starts with the premise that abstract art lacks archetypes, and that sets me off to the races, because I disagree with her.

Unlike Colleen, I come from the generation who went to school when representational art was verboten and we realistic artists had to make extraordinary efforts to understand the whys and wherefores of abstract art (while the abstractionists disparaged realistic art as the territory of the feeble-minded), so I’ve given this a lot of thought. Even without recognizable imagery, we make instinctive associations. Vertical implies a figure, a tree or a building. Horizontal implies land or an extent of water — a horizon. For instance, look at this Diebenkorn, above. It’s all rectangles but you’re going to see things in it. The blue might remind you of the light you saw on water, the ivory might remind you of a sand bar or maybe something completely different, but it will still tap into memories, even if you can’t pin down what you’re remembering. If you the abstract artist have elicited an emotion with abstract imagery, it is because you have still tapped into the subconscious, you have tapped into associations with shapes and juxtapositions or even light and shadow colors. You may think that with abstract art you have gotten away from archetypes but you haven’t.

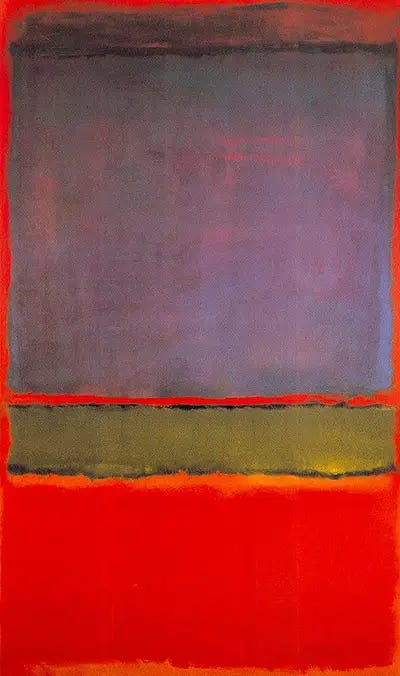

Look at Rothko, the spaces between his shapes are all about personal relationships, they’re close or their distant, they’re sharp or they blur. Even with abstract art, you really can’t get away from the narrative, you really can’t get away from how we see the world in terms of the physical and the story.

Even in something like Pollock, we look at the marks and even though it’s an allover pattern, that sends us to how the marks were made, you can’t look at a Pollock without seeing the action, it brings us to the archetype of the archer, the archetype of the scribe, the archetype of the hero searching in a cave, the cave of his unconscious, the archetype of the hero facing his internal dragons. The archetype is there but it isn’t in the painting, it’s implied by the painting. The painting is essentially the footprints left when the Archetype has passed through. The Abstract Expressionists liked to think they had transcended the archetype but they hadn’t; they had just obfuscated their archetypes. They made the archetypes harder to read but they’re still there. They might as well have stopped pretending they were so fricking advanced that they had transcended the archetype. Without associations, without any tether at all to the real world, we have nothing with which to construct meaning or even emotions.

Even if you think of 1970s grid paintings, they tell a story of an artist who was following the rules laid out by the critics, rules that demanded precision and intellectual rigor and emotional suppression, and if the painting still managed to elicit emotions, it is because associations still slipped through, triggering memories that may be so vague that they can’t be articulated, but those memories had associated emotions, and the emotions were still elicited. So for instance, this Slavin might remind you of dappled light. Who knows what place you associate with that dappled light, and you probably don’t consciously remember yourself, but the arrangement that reminds you of light and shadow and color reminds you of a mood you had, somewhere, even if you can’t pin down where it was. But that mood is there, and who you were when you first had that association is there. That combination of who you were and where you were is the piece’s archetype, it may just be beyond words.

The story is *always* there, if you just know how to read it, at least the feeling of the story. The archetype is *always* there, if you can just see it. It’s just that with representational work, the archetype is more obvious.

A given archetype might give you a certain mood. An abstract piece that conveys that mood but which is completely beyond words will put you in the same place in your psyche as that archetype.

Because realistic work is built on top of abstraction, that same wordless mood you achieved in the piece’s foundational abstraction will come through regardless of the recognizable imagery. A representational piece does not need to be read consciously to have meaning, to stir an association with an archetype. The wordless associations can be deeper than the things depicted, they can be in the light, they can be in the space.

How does an artist work with an archetype? They may consciously start with that archetype and explore it. They may stumble on it while groping around in the process of making their painting. Either way, the archetype is there and they work with it and they work through it, even if they’re not aware they’re doing so.

If it comes from a genuine need on the part of the artist, the conscious or unconscious exploration of a given archetype or the combining of archetypes is way more interesting than the unsuccessful attempt to run away from using archetypes at all. Because the why is always the interesting part. Why this archetype, and why now, why does the zeitgeist demand it. What life problem are you trying to solve, even if you’re not aware you’re doing it? Especially if you’re not aware you’re doing it. Why is this archetype relevant? Why do you care? Why should your viewer care? Does this archetype come up over and over? Archetypes are fascinating because of these questions. The effort to avoid archetypes is pretty pathetic because it’s like trying to run away from the fact that you’re human and you think like a human, it’s like trying to be hard and dry and dead like a computer.

Of course, there are people who decide intellectually they’re going to work with an archetype because everyone else is doing it and they pick one that looks cool or that everyone else is trying and they paint its surface and that’s the end of it. They may come up with some cool visual gimmick but frankly what they’ve devised is a party trick and they’ll have to come up with another gimmick next week. This is not the way you do it. I don’t care if you’re an abstract painter or a realistic one, if you work with something, be it an archetype or a color or a shape or a medium, it has to be from a real need, it has to be the only tool for the job.

An archetype is just a tool. It is an instrument for digging. Your time, your zeitgeist, the conversation you and your follow artists have from work to work, and you and your weirdness and your faults and your brilliance are the soil in which the digging is done. If you dig with courage and honesty, you might do good work.

Whether you dig with one style or another, whether you’re an abstract artist or representational, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that your style reflects the way you think. What matters is that your approach is a natural extension of who you are. What matters is that you’re brave and you’re honest, and you’re skilled enough in your visual language to get across what you’re trying to say.

And then you might get somewhere.

Go dig.

You can run from your humanity, hide in abstraction and cold intellectualism, but the narrative and archetypes are so baked into the way humans think that you cannot escape them.